When You’re in Love, with Louise Brooks, was released on this day in 1937. When You’re in Love is a romantic musical scripted and directed by long-time Frank Capra writer Robert Riskin and starring Grace Moore and Cary Grant. The enjoyable and fast-moving plot turns on high-spirits and high-notes. Louise Brooks makes an uncredited appearance as one of a number of dancers in a musical sequence near the end of the film. More about the film can be found on the Louise Brooks Society filmography page.

|

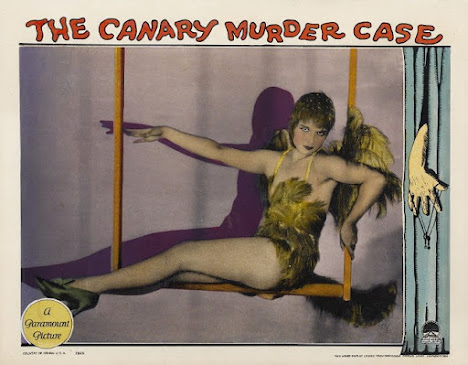

| Louise Brooks, third from the left, is obscured by Grace Moore's hand. |

Production of the film took place at Columbia Pictures studios in Southern California between October 5 and December 20, 1936 . The musical pageant at the end of the film, which likely includes Louise Brooks, was likely shot in part at the Hollywood Bowl.

For When You’re in Love, Brooks accepted work as an extra (its

almost impossible to spot her) with the promise of the feminine lead in

another Columbia film. To exploit the situation, the studio put out the

word that Brooks was willing to do anything to get back into pictures.

“Louise Brooks is certainly starting her come-back from the lowest rung

of the ladder,” wrote Wood Soanes of the Oakland Tribune. “She is one of a hundred dancers in the ballet chorus of Grace Moore’s When You’re in Love.” Brooks kept her part of the bargain, but the studio did not. Brooks’ lead in a Columbia film never materialized.

The film proved especially popular, and was seen as a worthy successor to Moore’s triumph in the 1934 film One Night of Love, for which she was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress. The Hollywood Reporter stated, “With a more substantial story than the last two Grace Moore vehicles, When You’re in Love is a signal triumph for the foremost diva of the screen, for Cary Grant who should soar to stardom as result of his performance in this, and for Robert Riskin, here notably handling his first directorial assignment.” The Hollywood Spectator added “It is unquestionably her best to-date and never has she appeared to better photographic advantage.” Rob Wagner, writing in Rob Wagner’s Script (a trade journal), was especially enthusiastic. “Here is the perfect combination – the director who writes his own script and delivers perfectly . . . Yes, I’m raving, … but because I’m a priest of beauty; and this picture thrilled me.”

The film was held over in New York City, as well as in Baltimore, Seattle, Detroit, New Orleans, Trenton, Tacoma, and Springfield (Massachusetts and Illinois). The same was true in Atlanta, Georgia. The Atlanta Constitution wrote that the film, the “best picture made by Grace Moore” was “now in its third week at the Rialto Theater, with the demand for seats showing no signs of easing.” The same was true in Hartford, Connecticut. The Hartford Courant wrote “Don’t look now, but Loew’s Theater appears to be starting another one of those record-breaking picture engagements with When You’re in Love.”

The great British novelist Graham Greene, writing in Night and Day, was tempered in his assessment. “Miss Moore, even in trousers singing Minnie the Moocher, can make the craziest comedy sensible and hygienic. In For You Alone, the story of an Australian singer who buys an American husband in Mexico so that she may re-enter the States where her permit has expired, Mr. Riskin, the author of Mr. Deeds and (let’s not forget) Lost Horizon, has tried his best to write crazily, but he comes up all the time against Miss Moore.”

Under its American title, documented screenings of the film took place in Australia (including Tasmania), Bermuda, British Malaysia (Singapore), Canada, China, Dutch Guiana (Surinam), Haiti, Hong Kong, India, Jamaica, Japan, Korea, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Palestine (Israel), Papua New Guinea, The Philippines, and South Africa. As well, it was once advertised in Canada as When You Are in Love. In the United States territory of Puerto Rico, the film was exhibited under the title Preludio de amor (Spanish-language press).

Elsewhere, When You’re in Love was shown under the title Le Cœur en fête (Algeria); Preludio de Amor (Argentina); Sérénade and Interlude (Austria); Sérénade (Belgium); Prelúdio de Amor (Brazil); 鳥語花香 (China); Preludio de amor (Cuba); Když vy jste v lásce (Czechoslovakia) and Ked si zalúbeny (Slovakia, unconfiirmed); Serenade (Denmark); Preludio de Amor (Dominican Republic); Ma olen armunud (Estonia); Rakastuessa and När man är kär (Finland); Le Cœur en fête (France); Otan i kardia ktypa (Greece); Közjáték and Preludio de Amor (Hungary); Serenade (Iceland); Amanti di domani (Italy); 間奏楽 or Kansō-raku (Japan); Wenn die Liebe erwacht (Latvia); Serenade (Luxembourg); Preludio de amor (Mexico); Le Cœur en fête (Morocco); Als je verliefd bent (The Netherlands); Forelsket (Norway); Kiedy jestes zakochana (Poland) and חפּחדדה (Yiddish in Poland); Prelúdio de Amor (Portugal); A rioi szerenad (Romania); Preludio de amor (Spain); När man är kär (Sweden); Le Cœur en fête and Wenn Du verliebt bist (Switzerland); Bir ask macerasi and Sen aska dusunce and Yalniz senin için (Turkey); and Preludio de amor (Uruguay).

The film was also shown under the title For You Alone in British Malaysia (Singapore), Ireland, and the United Kingdom (including England, Isle of Man, Northern Ireland, and Scotland).

SOME THINGS ABOUT THE FILM YOU MAY NOT KNOW:

— Grace Moore (1898–1947) was an American operatic soprano and actress in musical theatre and film. She was nicknamed the “Tennessee Nightingale.” During her sixteen seasons with the Metropolitan Opera, she sang in several Italian and French operas as well as the title roles in Tosca, Manon, and Louise. Louise was her favorite opera and is widely considered to have been her greatest role. Moore is credited with helping bring opera to a larger audience through her popular films. Moore died in a plane crash near Copenhagen’s airport on January 26, 1947, at the age of 48. Moore’s life story was made into a movie, So This Is Love, in 1953.

— Attracted to Hollywood in the early years of talking pictures, Moore’s first screen role was as Jenny Lind in the 1930 MGM film A Lady’s Morals. Later that same year she starred with the Metropolitan Opera singer Lawrence Tibbett in New Moon, also for MGM. After a hiatus of several years, Moore returned to Hollywood under contract to Columbia Pictures, for whom she made six films. In the 1934 film One Night of Love, she portrayed a small-town girl who aspires to sing opera. For that role she was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress. The last film that Moore made was Louise (1939), an abridged version of Gustave Charpentier’s opera of the same name, with spoken dialog in place of some of the original opera’s music. The composer participated in the production, authorizing the cuts and changes to the libretto, coaching Moore, and advising director Abel Gance.

— In the film, Moore sings “Siboney“. Xavier Cugat’s version of “Siboney” was recommended by Brooks in her self-published booklet, The Fundamentals of Good Ballroom Dancing.

— The New York Times noted that the lyrics of Cab Calloway’s “Minnie the Moocher” had been censored, writing “we did notice that the censors took out the reference to the King of Sweden who gave Minnie whatever she was needin’. Now it’s the King of Rythmania, who filled her full of vintage champagnia.” Although Daily Variety noted that preview audiences enjoyed Moore’s swing rendition of the classic song, it was not included in the general release print.

— Back in 2016, I wrote an article for Huffington Post on When You're in Love when it debuted on the cable station, getTV.

THE LEGAL STUFF: The Louise Brooks Society™ blog is authored by Thomas Gladysz, Director of the Louise Brooks Society (www.pandorasbox.com). Original contents copyright © 2023. Further unauthorized use prohibited.